Stand and Deliver! Dick Turpin and the Origins of True Crime

With the cancellation of Apple TV's Dick Turpin series, here's a potted history of the True Crime genre and the real Dick Turpin.

“Murder is always a mistake. One should never do anything that one cannot talk about after dinner.” – Oscar Wilde

But murder, violence and crime have been precisely the words on everyone’s lips for centuries. The recent surge in true crime content might feel new, but the only novel thing about it is the way in which it is consumed (podcasts, documentaries, online discussions). So, how did it all start?

The First True Crime?

When William Caxton launched the first printing press in England, in 1476, as well as triggering a revolution in the dissemination of ideas, information and news, he also marked a turning point in the way in which violent crime was reported and consumed. One of the earliest examples of printed murder pamphlets in England, for example, can be traced by to 1514. They focused on the death of ‘Protestant martyr’ Richard Hunne, who was believed to have been murdered by catholic church officials while in custody. It was the start of a trend that flourished throughout the century and beyond, becoming an established part of print culture.

In the second half of the 16th century, these stories swelled into another public space - the playhouse. Many of the leading figures from this time are still household names – Shakespeare, Marlowe, Webster and Jonson, to name just a few - and their plays are laced with stories of murder, violence and revenge. There are many examples, but I want to focus on a play that provides a crucial intersection between real crime and public entertainment - Arden of Faversham.

The First True Crime Phenomenon?

Arden of Faversham is a play (with debated authorship) that was published in 1588. It explores the story of Alice Arden who, through a variety of means and using a growing band of accomplices, attempts and then succeeds to murder her husband Thomas Arden so that she could be with her lover, a tailor named Richard Moseby. The play is based on a real case that took place thirty years earlier. Professor Catherine Richardson has quite rightly described the play as “the first extant domestic tragedy and the first true crime play and detective story”.

The real Thomas Arden was strangled and stabbed to death by his wife Alice in his own home on Valentine’s Day 1551. After being found out, Alice was convicted of Petty Treason and burned at the stake. Several accomplices were also executed. With its mixture of intrigue, extreme violence, the number of failed attempts, the scale of the operation and the foregrounding of a female murderer, the story quickly became famous and was picked up by numerous chroniclers and pamphleteers over the ensuing decades. Demonstrating its enduring appeal, a murder ballad relating to the case was registered with the Stationers Company well over a century after the crime had taken place (1663). The play itself is still performed, with a notable production in 2014 by the RSC. In the way it caught popular attention and traversed numerous mediums, the case of Alice Arden of Faversham, is arguably the first instance of a modern true crime phenomenon.

By the time we reach the so-called ‘long eighteenth century’, what we might today call the true crime genre had expanded beyond measure. Now, alongside gory tales on stage, moralising pamphlets and street ballads detailing the dreadful deeds of others, people could also consume books that cast criminal members of a growing urban underclass as folk heroes, and they could (and did) devour works that offered potted histories of infamous pirates, highwaymen and murderers. Among the most popular of these was A General History of the Robberies and Murders of the most notorious Pyrates (1724) by one ‘Capt. Charles Johnson’, which featured the stories of Anne Bonny, Blackbeard and the like. In truth, we do not know the authorship of the book. Some have argued it penned by Daniel Defoe or Nathaniel Mist, others that the writer was a Jacobite sailor.

What is certain is that the book was so successful that within two years it had run to a fourth edition. In 1734, it was followed by A General History of the Lives and Adventures Of the most Famous Highwaymen, Murderers, Street-robbers, &c, which looked at the likes of highwayman William ‘The Golden Farmer’ Davies and James Hind. It was into this cultural landscape that Dick Turpin emerged. Both the real man and the folk hero.

Enter… Dick Turpin

Let’s look at the real individual first. Richard Turpin was born in Essex, England, in 1705. He was the fifth of six children to butcher John Turpin and his wife Mary Elizabeth Parmenter. By 1725 records suggest Richard Turpin had followed his father’s trade, setting up as a butcher in Buckhurst Hill, Essex, with his wife Elizabeth Millington. A decade later, Turpin became associated with a group of criminals known as the Essex / Gregory Gang, who would steal and sell animals (deer, horses, etc) for profit. It might be that as a butcher Turpin had contacts that were useful to the Gang. We don’t know. What we do know is that overtime his loose association with the Gang became more fixed and he was directly involved in many of their crimes (according to the late historian James Sharpe, for example, he was part of the group who raided the home of a 73-year-old farmer named Ambrose Skinner to the tune of £300).

Without going into every twist and turn, suffice to say that the Gang imploded. A mixture of infighting, collisions with the authorities, and subsequent hangings and transportations meant that Turpin was left to his own devices. It is at this juncture that he appears to have started engaging in what history has remembered him for – highway robbery. With a rogue’s gallery of accomplices, he robbed coaches in Epping Forest, Barnes Common and Hounslow Heath, earning him the moniker ‘Turpin the Butcher’ and the attention of the authorities.

Unlike the French Marshalcy across the channel, there was nothing that we would recognise as a modern police force operating in England at this time. Even the Bow Street Runners wouldn’t come into being until 1749. Instead, people were policed by constables, informers, thief-takers (some of whom are very unsavoury characters), and opportunists, before being turned over to the magistrate. Rewards were an important method of catching criminals and £100 bounty was put on Turpin’s head.

As a wanted man, he was on borrowed time, especially as he continued to engage in criminal activity. In 1736, he narrowly avoided capture at an inn in Puckeridge, Hertfordshire, when his letters were intercepted. Then, early in 1737, he was almost caught in Leytonstone by a local landlord who was hot on his trail of after being told that a local man’s horse had been stolen. During his escape from the landlord, one of Turpin’s accomplices, Matthew /Tom King, was fatally wounded by a gunshot. After this, Turpin went into hiding in Epping Forest only to be discovered once more. This time by Thomas Morris, a servant of the forest keeper, who Turpin shot and killed before escaping again.

He was finally apprehended in Brough, Yorkshire, after shooting another man’s gamecock in the street. He told authorities that his name was John Palmer and that he was a butcher who’d fallen on hard times. But when the justices of the peace made enquiries, it became clear that ‘John Palmer’ was actually involved in criminal activity, including stealing sheep and horses, the latter of which was a capital offence. Refusing to pay the surety, he was transferred from the House of Correction in Berkeley to York Castle. While he was awaiting trial, still under the alias of John Palmer, Turpin wrote a letter to his brother-in-law in Hempstead, Essex. But when it arrived at the local Post Office, Turpin’s brother-in-law refused to pay the fee, claiming that he didn’t know anyone in York. The letter was then sent to the Post Office in Saffron Walden where, in a twist of fate that would be unbelievable in a novel, the man who had taught Turpin to write as a child recognised the handwriting. His name was James Smith, and he was granted £200 for travelling up to York and formally identifying John Palmer as Richard Turpin.

Turpin was tried for horse theft in York, found guilty and sentenced to death. He bought himself a new outfit for the fateful day and hired five mourners to follow his cart as it made its way through York to the gallows at Knavesmire where he was executed by hanging on 7 April 1739. As the real man died, a legendary figure was born.

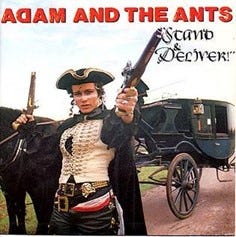

Remember the landlord who almost captured Turpin in Leytonstone? His name was Richard Bayes and in 1739 he wrote and had published The Genuine History of the Life of Richard Turpin. It was the first of many semi-fictional accounts of ‘Dick Turpin’, the infamous highwayman. There are plenty of things about Turpin’s real story that are interesting - from his numerous escapes to the vanity of hiring five mourners. There are also aspects that are very dark - killing another man, abandoning his wife, targeting the vulnerable. But most of the darkness is lost in the fictional Dick Turpin and replaced with romance and adventure. The real Richard Turpin did not make the fabled overnight ride from London to York on a horse called Black Bess. That story was the creation of 19th century writer, William Harrison Ainsworth in his book Rookwood, who in turn seems to have been inspired by the story of William Nevison written by Daniel Defoe in 1727. Nevertheless, Dick Turpin the highwayman became a cultural lodestone. Like Alice Arden before him and many true crime figures after, he’s become the archetype of his ilk, whose story has been romanticised in literature, in music and onstage and on screen for nearly three centuries.

There have been countless psychological studies into society’s obsession with true crime. Recently, Coltan Scrivner from the Recreational Fear Lab argued that there is a learning component to true crime in that it makes us feel more ‘prepared’ for dangerous situations. But I think with Dick Turpin - the character rather than the real person - there is an element of rooting for the underdog. He has become an almost Robin Hood figure. Perhaps The Completely Made-Up Adventures of Dick Turpin character Eliza Bean sums it up best: ‘I think people are just fascinated by criminals’.